What does nature mean to you? It’s a very simple question. But nature means many different things to many different people. In Aotearoa New Zealand the case of Te Urewera requires us to think about relational values and questions of environmental justice. It also challenges us to think carefully about national parks as a form of colonialism.

Transcript

What is nature?

Why is nature important?

And are humans part of nature or separate from nature?

The answers to these questions are wide ranging. Which is to be expected, because everyone will have their own opinions, shaped by culture, personality, upbringing, religion and personal experiences. The ways in which people value nature also shapes the way that people think about nature tourism, specifically:

- How should nature be used (or not used) for tourism?

- Does tourism protect nature, or pose a threat to nature?

- And who holds the power to decide how nature is used for tourism?

These are also questions that raise a range of opinions which in turn raise more questions:

- How inclusive is nature conservation?

- Who’s ideals of nature are upheld and supported

- And who’s ideals of nature are suppressed?

These questions are anchored in the field of environmental justice. Because decisions on these sorts of questions prioritise some versions of nature over others, include and privilege some people – often international tourists – and exclude and oppress others – often indigenous people who have in the past in many parts of the world been physically and spiritually removed from nature in the interests of conservation and tourism.

****

Some of these points are illustrated in the case of African game parks. I remember as a student reading a paper that investigated the virtues of national parks in Africa and the conservation of big game species, specifically the “Big Five” – Lions, Leopards, Rhinos, Elephants and African Buffalo. So who decided that these were the big five – because being included or excluded could be good or bad news – depending on the purpose of this classification. If this meant extra value and therefore protections then good news for those included. And therefore bad news is you were excluded – a giraffe, zebra, or hippopotamus. Or an antelope, hyena or warthog.

You would be forgiven for thinking that the “Big Five” are the African animals that tourists most want to see and photograph. No, not so. The “Big Five” were actually named by 19th century European hunters – they were the five animals that were considered most dangerous and challenging to hunt on foot. The term is still used by safari-goers today although the focus has generally shifted from shooting with guns to shooting with cameras – although trophy hunters still prefer to shoot with guns.

The idea of the “Big Five” shows how nature has been categorised and valued in the past.

The article critically examined the designation of national parks in African countries as tourist resources for predominantly European safari goers. It pointed out the argument that national parks are often designated as a resource base for development of the tourism economy. Under this line of thinking, nature should be protected as a tourism resource, to cater for the interests of foreign visitors.

The article did point out two problems with valuing and protecting nature for tourism. Firstly, foreign tourists want to see natural nature – they imagine viewing African wildlife in the complete absence of African people. So the designation of African national parks has historically usually required the physical displacement and therefore disempowerment of traditional African tribal communities.

And second, it pointed out the development of a tourism economy is often associated with the rapid development of international supply chains, including international travel agents, international airlines, international hotel chains, and international hospitality supply chains. The paper noted that less than one cent of every dollar spent by tourists remained in the destination economy. Kenya and Tanzania soon came to serve as a places of tourist production within a global tourism economy that left local residents in poverty. These were arguments against the theory of trickledown economics.

So I have had a somewhat cynical view of national parks for some time. Not that they are a bad thing necessarily. National parks and conservation management do of course serve important roles, if managed for conservation in perpetuity. But it is of course more complicated than this.

****

These debates take me back to my PhD in the School of Geography at the University of Otago in the mid-1990s. My PhD was on international tourism and wilderness perceptions and it was a great topic for the same reasons – the way that people think about wilderness varies with individual first-hand experiences of nature, which vary enormously among tourists of different nationalities.

My PhD included a review of the history of human relationships with nature, from the Palaeolithic to the present. A book on this subject written by Max Oelschaelger was published a few months before I started my PhD. It was titled The Idea of Wilderness: From Prehistory to the Age of Ecology. It was a meticulously researched and detailed book. It noted that the Palaeolithic mind did not distinguish humanity from nature, but did wonder about the miracle of creation. Humans were part of nature and indistinguishable from nature. Gods were created in the image of game animals such a bulls and bison as depicted in Palaeolithic cave art.

It was Judeo Christianity and the emergence of Gods that were created in our own image and likeness that initiated the process of distinguishing humans from nature. It was as if humans stepped out of nature and turned around to look back at it. Domestication, agriculture and sedentism further entrenched this separation. Nature became viewed as a stockpile of resources for humans to exploit. God gave humanity the mandate to “be fruitful, multiply, fill the earth, and subdue it”. In the Bible (Genisis 1:26-30) God granted humans dominion and authority over the fish of the sea, the birds of the air, and every other living creature that moves on the earth.

Nature became viewed as the antithesis of civilisation. A failure of God’s mandate. Civilisation was considered to break down at the wilderness frontier. Wilderness was a wasteland waiting to be civilised and brought under control.

In Europe these views of nature began to be challenged during the Age of Enlightenment in the 16th and 17th centuries and with the rise of Modernism. At this time in Europe wilderness started to become viewed romantically as places of profound spiritual value and aesthetic experiences. The 19th century Romantic movement emphasised the concept of the sublime. Wilderness began to inspire feelings of awe at the powers of nature, offer solace from modernism. Nature became necessary counterpoint to disorder of urbanisation, industrialisation and pollution – processes that not only represented the ultimate separation from nature but also the ultimate exploitation and destruction of nature.

These changing environmental values had a heavy bearing on colonial expansion. Oelschlaeger reflected on the concept of wilderness in Europe when European settlement of North America. Colonisation in this case predated Modernism. At the time, according to Roderick Nash (1980), attitudes towards wilderness in Europe were still dominated by the Judeo- Christianity. Colonists brought with them a value system based on survival to which wilderness was considered a threat. Morality and social order were considered to break down at the North American frontier, beyond which “forests swarmed with demons and evil spirits”.

This was of course bad news for the indigenous North American Indian tribes that had lived in peace in North America for millennia, using a 26 fortnights lunar calendar linked to nature’s changing seasonal bounties. With colonisation Indian tribes were viewed as a constant threat in the minds of colonists who viewed wilderness as a “cursed and chaotic wasteland”. They thought that civilisation was engaged in a ceaseless struggle to bring nature under control, and that it was God’s will to tame the wilderness.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when systematic colonisation of New Zealand began, the seeds of Modernism had been sown in Europe. The natural environment was new and alien to European colonists and still seen as a threat to survival. Native lowland forested lands were cut and burnt in order to open opportunities for farming. Yet there is evidence to suggest that the colonists brought to New Zealand attitudes toward wilderness that contrasted the American situation.

Industrial cities in Europe had come to be seen polluted and toxic. This, according to historian Erik Olsen (1990), “reflected the widespread belief that cities and towns were cancerous cradles of crime, sin, disease and vice”. The European pioneers remained utilitarian in their attitudes towards the environment. The wealth generated by agriculture convinced most of the moral superiority of the family farmer. Most of our remaining wild land protected under some form of reservation today is in fact mountain land unsuited to any form of agriculture.

Despite this, areas such as Fiordland and the Southern Alps were explored and valued for their scenic qualities. “Manapouri, with its wooded islets and peninsulas and fantastic bays and coves, and its girdle of high mountains and waterfalls is… an inspiration… to every beholder”, so said James McKerrow in 1862.

The qualities of nature so valued by European colonists is confirmed by the designation of extensive areas for protection. The establishment of a Scenic Preservation Commission, the recipient of multiple recommendations between 1903-1906, affirms the Modernist perception of wilderness in the minds of European settlers. This is further verified by the designation of National Parks, Tongariro in 1887 and Fiordland in 1905.

This marks a transition of attitudes toward nature from one of ‘anti-wilderness’, through ‘sublime, picturesque and romantic nature’ and ‘outdoor recreation’, to ‘conservation and protected areas’. Commonly referred to as the transition from ‘wasteland to world heritage’ – national parks in New Zealand were gazetted with their value as a resource for outdoor recreation and international tourism front of mind. National Parks became preserves of naturalness that could serve a utilitarian function, as the resource for tourism development.

****

So wilderness, national parks and imperialism are closely tied together. New Zealand was the second country in the world to designate a national park, after Yellowstone National Park was established by the US Congress in 1872. New Zealand borrowed heavily from American national parks and wilderness legislation. Our adoption of North American definitions of wilderness and national parks is also a form of colonialism.

The definition of wilderness in New Zealand is drawn from The Wilderness Act 1964 (USA) which specifies wilderness as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammelled by man, where man himself is the visitor that does not remain”. That is a statement that fundamentally disconnected and from Te Ao Māori – the Māori worldview, encompassing tikanga (customary values), mātauranga (knowledge), and the interconnectedness of people and the natural world.

Wilderness in the US, therefore, is “undeveloped Federal land retaining its primeval character and influence… which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions”. Of course in North America, the designation of the world’s first national park – Yellowstone – conveniently ignored the fact that indigenous tribes including the Kiowa and Blackfeet among many others, had lived in the Yellowstone so-called ‘wilderness’ for approximately 12,000 years, since the end of the last ice age, when humans first appeared in the archaeological record in North America.

That long indigenous history was incompatible with Europe ideals of national parks, and so the tribes were forcibly removed to reservations, dispossessed, and disconnected from nature – to establish the myth of national parks as ‘empty nature’.

****

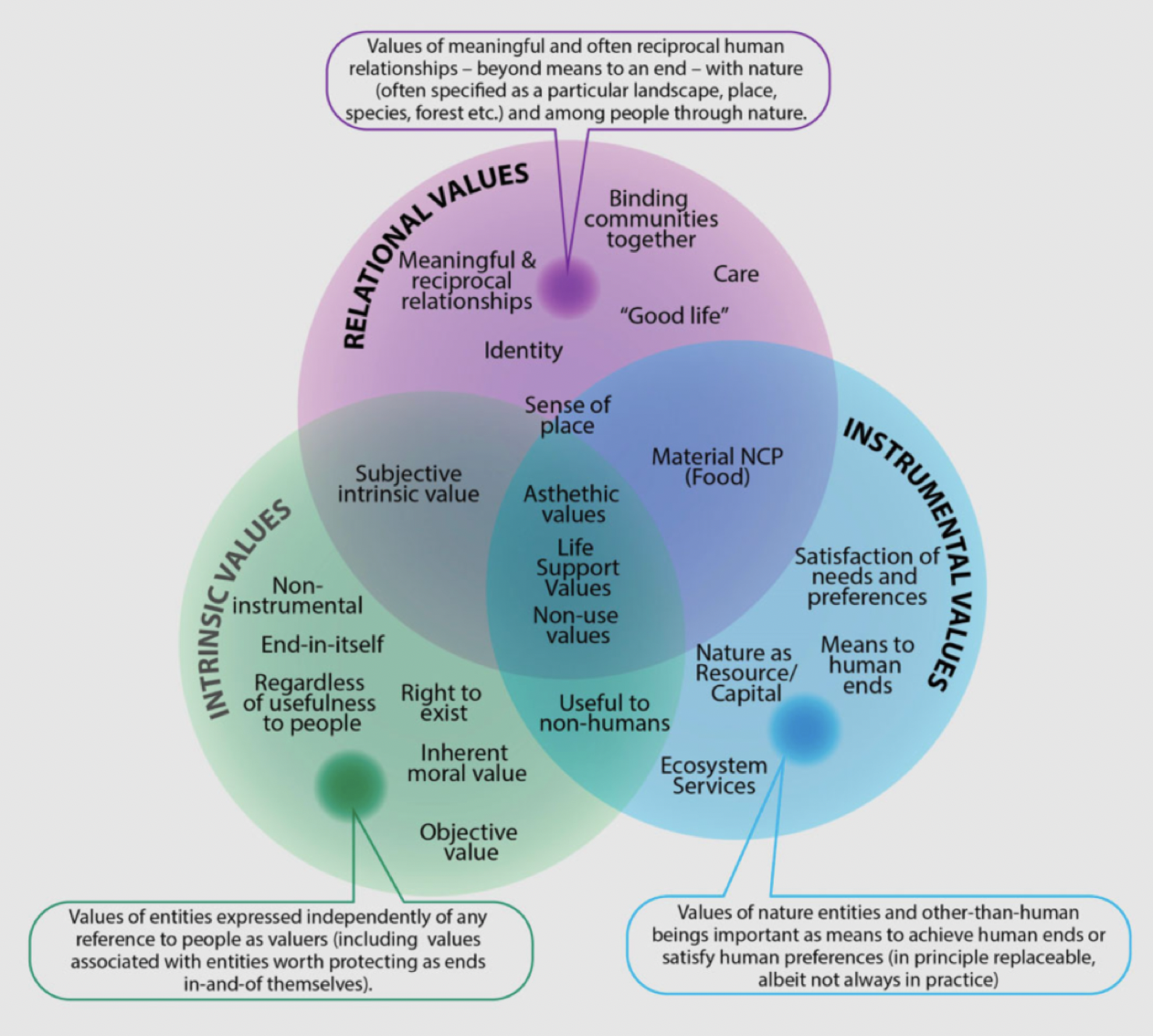

This history of nature, dispossession and separation raises important questions about how we value nature. This question is very useful addressed in a paper published last year by Austin Himes from Washington State University, and his co-authors. The authors note that the way that individuals, communities, and societies express the importance of nature – and people–nature relationships – take many forms that are reflective of contrasting worldviews, and are important in terms of policies that define how nature contributes to people’s lives and to society.

They identify three sets of values:

- Intrinsic values: express value in nature independently of any reference to people. Nature is viewed as an end in itself, regardless of its usefulness to humans. Nature therefore has moral value and a right to exist for its own sake.

- Instrumental values: express value in natureas an important means to achieve human ends or satisfy human preferences. This may include nature’s utility value in terms of ecosystem services, asset value, capital or property, and includes the protection of nature for tourism.

- Relational values: express value in nature in meaningful and reciprocal human relations, beyond a means to an end. Such values may include cultural identity, serving as a point of connection among people, binding communities together.

Relational values are associated with indigenous thinking which does not accept the separation of nature and humanity but rather sees humans as part of – and inseparable from – the Earth, sea and sky. Interestingly, the literature on relational values has only really emerged in very recent years but the importance of relational values has been quickly recognised. This literature emphasises relationships of responsibility, stewardship and care, harmony with nature and justice.

Source: Hines et al. (2024).

****

So what do relational values mean for tourism? Regenerative tourism is founded on the principle that tourism should give back more to people and places than it takes. It should empower local people rather than disempower or oppress which has been a common consequence of tourism globalisation. Central to this is recognition that destinations are part of living systems where people and ecosystems exist in relationships that are deeply connected. Tourism, therefore should contribute to rebuilding and strengthen relationships between people and place, culture and nature.

According to the Māori worldview, nature is not a resource to be exploited in Western utilitarian terms, but a living ancestor. So regeneration is not just about fixing damage but about restoring kinship relationships that extend across generations past, present and future. According to the Māori worldview, protecting nature is a way of restoring the whakapapa (ancestry) of that place by expressing connection to the whenua, kaitiakitanga (responsibility for its care), and maintain respectful relationships with nature among mana whenua and manuhiri (visitors or guests).

****

Aotearoa New Zealand has been a world leader in relational values, none more so than the case of Te Urewera. Established as a National Park in 1954 Te Urewera became New Zealand’s fifth national park. With further land acquisitions in 1962, 1975 and 1979, it became the largest national park in the North Island. It includes Lake Waikaremoana which was one of New Zealand’s 11 official Great Walks. As part of the system of National Parks in New Zealand it was managed for conservation, as well as recreation and tourism, with low levels of facility development and the general absence of humanity, where people visit but do not remain in the National Park.

Te Urewera National Park was created to remain a national park in perpetuity, guaranteeing its protection for future generations. However, in this case perpetuity lasted only 60 years. Tūhoe is the Māori iwi (tribe) connected to the mist-shrouded Te Urewera region. Tūhoe has a rich history of resistance, strong cultural traditions, and a deep connection to their ancestral lands. In March 2013 Tūhoe signed a deed of settlement under Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Under the Te Urewera Act 2014 Te Urewera was granted the legal status of a person. It can not be owned. Te Urewera ceased to be a National Park under the ownership of the Crown.

Instead it is protected under the guardianship management of Tūhoe who give expression to the living qualities of nature in accordance with Māori perspectives. These qualities are protected by law.

So in 2014, in a world first, Te Urewera was disestablished as a national park and redesignated a ‘legal entity’.

Tongariro National Park, New Zealand’s first national park was gifted to the Crown in 1887 by Ngāti Tuwharetoa to protect the volcanic peaks of Tongariro, Ngauruhoe, and Ruapehu in perpetuity. Tongariro was designated UNESCO’s first World Heritage ‘Cultural landscape’ in 1993, highlighting the fact that its natural and culture values were inextricably integrated. Tongariro is a place of profound spiritual significance for Māori. Its peaks are sacred ancestors that are revered as deities in Māori lore. They connect Ngāti Tuwharetoa to their ancestors and the gods. The mountain peaks are Tapu and should not be climbed.

Ngāti Tuwharetoa are the Tiaki or Guardians of the national park responsible for protecting its natural and cultural values. Local Tiaki Guides provide unique cultural insights to protect the cultural and natural values of Tongariro National Park.

****

The way we value nature raises important questions of cultural empowerment, integrity and authenticity. How are different world views presented, represented and interpreted? Who’s values and beliefs are shared… or withheld and suppressed?

Needless to say, that the separation of humanity from nature has gone hand in hand with the destruction of nature, through dominion of the fish of the seas, fowl of the air and beasts of the land, leading to ecological destruction, biodiversity loss and climate change. The designation of national parks under the North American model entrenches this separation of humanity from nature

By contrast, Te Urewera and Tongariro are examples of the status of nature as a living entity in accordance with Māori understandings of being part of nature, not separated from or elevated above nature.

In 1900, Āpirana Ngata, the Ngāti Porou leader and scholar, wrote of mātauranga Māori and mātauranga Pākeha and the great benefit of “casting our nets between them”, rather than fishing in one or the other. Inspired by his wisdom, there is much to be gained from adopting relational values in the management of National Parks, accepting that humans are inseparable from nature in every way, as a pathway towards decolonising National Parks in Aotearoa New Zealand.

References

- Hall, C. M. (1992). Wasteland to World Heritage: Wilderness Preservation in Australia. Melbourne University Press.

- Higham, J.E.S. (1998). Sustaining the physical and social dimensions of wilderness tourism: the perceptual approach to wilderness management in New Zealand. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 6(1), 26-51.

- Himes, A., Muraca, B., Anderson, C. B., Athayde, S., Beery, T., Cantú-Fernández, M., … & Zent, E. (2024). Why nature matters: A systematic review of intrinsic, instrumental, and relational values. BioScience, 74(1), 25-43.

- Nash, R. 1982. Wilderness and the American Mind (Third Edition). Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Oelschlaeger, M. 1991. The Idea of Wilderness: From Prehistory to the Age of Ecology. Yale University Pres. New Haven and London.