Our most visited places depend on ecosystems that are fragile, slow to heal and central to our collective wellbeing. So how can tourism shift from drawing on these ecosystems to actively nourishing what feeds us?

Transcript

In Aotearoa New Zealand, regeneration begins with the lands and waters that sustain us. And when we speak of regeneration, we inevitably turn to ecological restoration – the slow, careful work of helping ecosystems, species and relationships recover. Restoration is not simply planting trees or counting carbon. It is the practice of repairing connections between people and place, between species and their habitats, and between past, present and future. Through whakapapa, these connections recognise every living being as taonga. So for tourism, the question becomes: how might regenerative tourism support the restoration of ecosystems, and the restoration of our responsibilities to those who have long cared for these places?

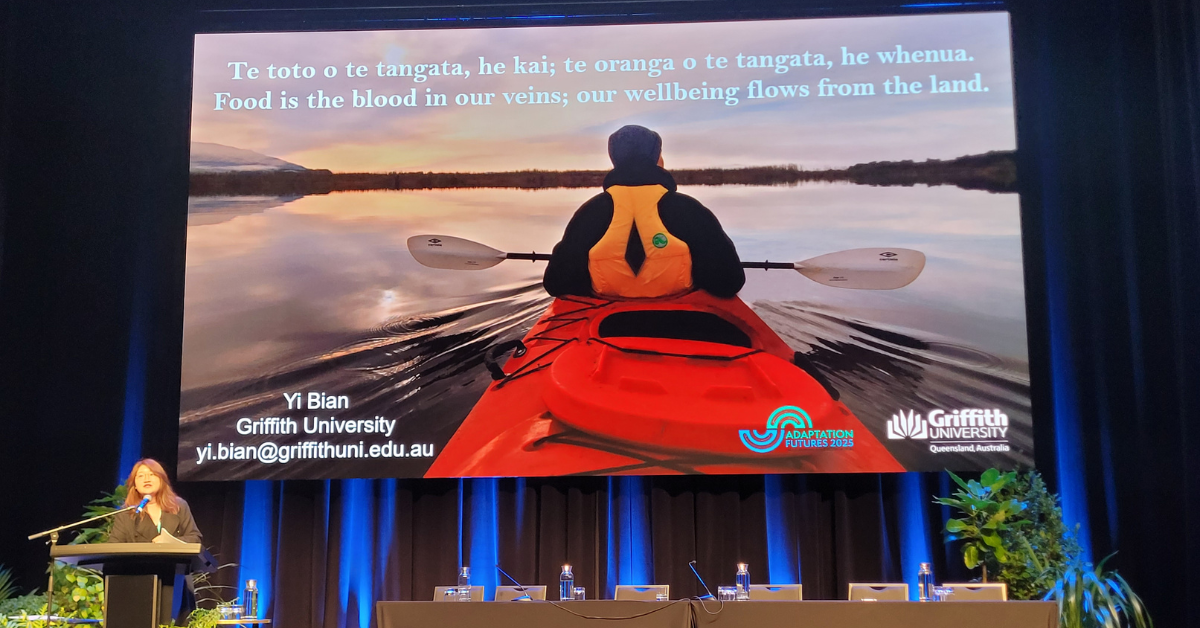

Today I am speaking with Yi Bian, a third-year PhD candidate at Griffith University whose research explores how ecological restoration and regenerative tourism can work together to address climate change and biodiversity loss in Aotearoa New Zealand. Her doctoral work is guided by a unique supervisory team spanning human geography, plant ecology and political philosophy, which shapes her interdisciplinary approach to regeneration. Over the past two years, she has carried out fieldwork across four restoration sites in Coastal North Otago, including forests, coasts, wetlands and rivers, working alongside iwi and hapū guardians, tourism operators, conservation groups, and government department staff.

In October, Yi travelled to Christchurch for the Adaptation Futures 2025 conference, the world’s leading climate adaptation event co-hosted with the UNFCCC. There she presented the first paper from her PhD, sharing insights from her fieldwork on how mahinga kai (the Māori practice of caring for food-gathering places) can guide policy and practice to support regeneration and avoid maladaptation. I am delighted that today she joins me to talk about her research.

What first drew you to study regenerative tourism and ecological restoration?

Back in 2021, during the pandemic, I was doing my master’s degree at the University of Otago and I took your course TOUR422, titled Tourism and Global Environmental Change. That course really changed the way I saw tourism in New Zealand. Because of our global location and distance from major international markets, most people have to fly to New Zealand to visit. The more tourists come, the more emissions they produce, and the worse climate change becomes. Then biodiversity declines faster, and yet biodiversity is exactly what attracts people to New Zealand in the first place. It felt like such a contradiction.

Around that time, the idea of regenerative tourism started to get attention in New Zealand. People began to realise that just being sustainable or reducing harm was not enough to fix the deeper problems in the system. I also noticed that tourism focused a lot on individual species but rarely talked about local ecosystems, which are also important carbon sinks. So I began to ask how restoration could connect climate, biodiversity, and tourism in a regenerative way. And of course, that raises the question of what we mean by regenerative tourism in the first place.

So what is regenerative tourism and how is it different from sustainable tourism?

Sustainability is often explained as meeting our needs today without harming the ability of future generations to meet theirs. Regeneration goes further. It is about improving places so that future generations inherit healthier forests, cleaner rivers and stronger communities. It is tourism that gives back more than it takes.

Your research is informed by Māori concepts such as kaitiakitanga and mahinga kai. For listeners who may not know these terms, can you explain what they mean and how they shape your work?

When I was doing my master’s degree, a lot of my Kiwi classmates would talk about kaitiakitanga, which means guardianship. But at that time I didn’t really understand what that actually meant.

It only became clear when I went into the field and worked alongside local kaitiaki or guardians. They showed me that kaitiakitanga isn’t about owning or managing land. It is about caring for it because you are part of it. Many Māori communities lost legal ownership of their land through colonisation, but they still keep looking after it. In the Māori worldview, everything is connected – people, rivers, birds, forests – and those connections come from our ancestors. That’s whakapapa, the idea that we are all part of the same family of life.

My participants also taught me about mahinga kai, which means food-gathering places. But it’s more than that. If we can still harvest healthy food, it means the land and water are healthy, biodiversity is strong, carbon is being stored, and our relationship with the ancestors is still alive.

You spent months in the field working alongside iwi and hapū kaitiaki, tourism operators, and conservation groups. What were some moments that stood out to you during your fieldwork?

One place that really stayed with me is Pukekura, where the local community cares for the little blue penguins. These penguins nest under coastal vegetation, so everyone has been working hard to restore the coastal ecosystem.

But it’s not easy. The strong coastal winds and high salinity make the soil challenging for replanting, and many of the young trees that people plant die every year. So the community keeps planting again and again. We often imagine regeneration as something full of hope, but what I saw was that regeneration also involves constant loss and death.

Still, because of this ongoing care, kaitiakitanga, the penguin population has slowly increased. It’s a sign that the work is making a difference, but it’s also a reminder that if we don’t deal with climate change, the current recovery could be in vain.

At Adaptation Futures 2025, you presented on maladaptation in regenerative tourism. What is maladaptation and what does it look like in this context?

Maladaptation is when something looks helpful at first but actually ends up causing harm to the environment.

In New Zealand, a really clear example is the planting of exotic pine trees for carbon credits. On paper it sounds great because you’re capturing carbon, but in reality these pine plantations are monocultures. They reduce biodiversity, attract pests, increase fire risk, and they’re not great for water systems. Pine trees also grow really fast, around thirty years, but native forests that support biodiversity can take eighty to a hundred years to mature and the restoration of native ecologies will take millennia.

So we end up trading long-term ecological integrity for short-term carbon gains. That’s a very typical form of maladaptation here. It’s a reminder that we need to move beyond carbon as the only measure of regeneration and look at how ecosystems and communities flourish together.

How can policy and industry better recognise mahinga kai when designing tourism or restoration projects?

I think it starts with understanding that mahinga kai isn’t just about food. It is a way of measuring the health of land and water, and the relationships that sustain them. If people can still gather healthy food, it means the ecosystem is working. Biodiversity, carbon, and culture are all in balance.

Right now, policy often focuses on metrics like carbon or visitor numbers, which are easy to count but miss the deeper relationships. Mahinga kai gives us a biocultural indicator. It connects ecosystem health with social and cultural wellbeing.

So instead of designing projects from the top-down, I think we need to listen more to the communities who already practise mahinga kai. Their knowledge can tell us what regeneration looks like on the ground, in the soil, in the water, and in everyday life.

You often say that regeneration is about relationships. What does that mean to you and what gives you hope about the future of regeneration in Aotearoa?

I think we often see development and conservation as opposites because we keep thinking of ourselves as something separate from nature. The Māori world view reminds us that everything is connected and that we all belong to the same living system. In that sense, restoration is not about choosing one thing over another. It is about collective flourishing. Forests, rivers, and birds are part of our extended family through whakapapa, so it does not make sense to harm our relatives for profit.

For me, regenerative tourism is about repairing our relationship with our ancestors. This feels especially important now, when climate change is getting worse and local accountability is often lost in global targets and big promises. Regeneration brings our attention back to everyday life to how we live, eat, travel, and care in the places we call home. When we start to see the world through relationships instead of numbers, that is where the real hope for regeneration begins. Which is why the Adaptation Futures conference was such a powerful moment for me.

So what were your reflections on the Adaptation Futures conference, and what do the months ahead hold for your PhD?

Adaptation Futures gave me a lot to think about. What stayed with me most was how often our challenges come from the systems we create. Sometimes the problem is not why people make the wrong decisions, but why the system leaves them with so few choices that honour their relationships with place. That reminded me that adaptation is not only technical, but also about creating the conditions for care. In thinking through these questions, I often find myself lucky to have my three supervisors, whose diverse backgrounds help me see how scientific understanding, relational thinking and ethical reflection can work together in this space.

For my PhD, the months ahead are really about thinking more closely about how our systems shape what we see as possible in the name of regeneration. I am finishing my papers on ecological restoration and regenerative tourism, but the deeper work is to understand the kinds of reasoning that guide our decisions and the values that sit quietly behind them. Technical fixes matter, but they can crowd out the ethical questions about what we owe to places, to each other, and to future generations. For me, regeneration is an ethical question about how different ways of valuing the world can sit together and how we create the conditions for a shared commitment to let life flourish. And I hope my work can be small way of giving back to the places and communities that have taught me so much.

Ngā mihi – thank you Yi. I am delighted to have you share insights into your PhD via my podcast. Congratulations on your PhD pathway to this point and the success of your conference presentation at Adaptation Futures. And best wishes for the completion and submission of your PhD for examination in mid-2026.

****

Yi’s PhD is supervised by Professor James Higham, Professor Brendan Mackey at Griffith Climate Action Beacon, and Professor Elisabeth Ellis at the University of Otago. For more on Yi’s research, including a summary of her PhD work and links to her presentations and publications as they emerge, please see the transcript on my website jameshigham.com/pod.

You can also contact Yi at yi.bian@griffithuni.edu.au

References:

Bian, Y., Higham, J., Ellis, L., & Mackey, B. (2025, Oct 13-16). Ecological Restoration as Mahinga Kai: Policy Pathways to Avoiding Maladaptation in Regenerative Tourism in Aotearoa New Zealand [Conference presentation abstract]. Adaptation Futures Conference 2025: Accelerating Adaptation Action, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Bian, Y., Higham, J., Ellis, L., & Mackey, B. (in press). Structural issues of biodiversity in tourism and climate justice. In R. Rastegar & S. Seyfi (Eds.), A Research Agenda for Just Tourism Futures. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bian, Y., Higham, J., Ellis, L., & Mackey, B. (in press). Representational issues of CO₂ in tourism climate equations. In J. Wen, M. Kozak, J. Aston, & W. Wang (Eds.), Interdisciplinary Tourism Research: An Intellectual Feast. Routledge.